The Tattoo Machine

Originally written for Tattoodles.com in 2005 these articles detail the history of the tattoo machine, tattoo history and methods and health issues associated with tattooing.

It's a very curious device, its origins lie in the first practical use of an electric motor, a great American inventor and the cooperation of craftsmen from both sides of the Atlantic.

The Industrial Revolution in both the U.S.A and the U.K. (1750-1915) brought with it an increase in population and urbanization, as well as new social classes. The manufacturing cities exported their goods via ships all over the globe and tattooing was a regular pass time amongst the sailors on long ocean journeys. The working class of the factories, mills and mines were exposed to the tattooing practices of the sailors and merchant navy in the taverns, markets and gambling houses of the day. All tattoos were applied by various hand methods inspired by the native practices of distant lands but, as with most other hand made artisan practices, tattooing would soon be mechanized.

Thomas Alva Edison is often referred to as the father of the modern electric tattoo machine. It would be a little more accurate to call him the grandfather of the tattoo machine.

In 1875 there had yet to be a use for this new invention called the electric motor, capable of transforming electrical current flow into rotary motion. Perhaps it was the pistons used on the wheels of steam trains that gave Edison the idea to transfer the circular, rotary action of the electric motor to a linear motion that could be applied to some purpose. But what could that be?

The very first invention to use an electric motor was known as the Autographic Printing Pen (Patented in the U.S. Aug.8th 1876).

What a very practical idea Mr. Edison.

This device would speed up the printing process by puncturing holes in a stencil, through which ink could be pressed onto a sheet of paper below.

The machine consisted of a heavy electric motor on the top of a pen barrel or tube. The needle (there was only one, thick steel needle) was driven up and down through the barrel, engraving the stencil plate below with a series of holes following the required design or lettering.

This was an effective use of the electric motor but not a user friendly one. It was cumbersome and difficult to work with for any extended period of time. Curiously Edison marketed the device, which sold well in America, even after he had designed improvements two years earlier in England (Patented in London Oct. 29th 1875 and in the U.S. Nov.6th 1877) By using two electromagnetic coils (a tightly wound copper wire around a soft iron core forming an electro-magnet), springs and contact bars the machine was lightened considerably.

Electromagnetic coils were widely used in telegraph instruments such as Morse's Repeater of 1836 and would prove to be vital in the development of the tattoo machine.

The issue of weight must have haunted Edison because he further revised the Engraving Pen doing away with the battery, which would seem giant by today's standards, and inventing The Perforating Pen (May 7th 1878) using a treadle mechanism powered by the operators foot much the same as a sewing machine or early dentists drill, and finally the Edison Pneumatic Stencil Pen (Jun. 25th 1878) using air pressure, gas or a liquid that could turn a fan system and drive the needle bar making the machine lighter and easier to use than the previous incarnations.

He did not, I'm sure, see the potential for a tattooing device.

That fantastic leap of vision was left to Samuel O'Reilly, a tattooist in New York City. All tattooing was hand poked, prodded and scratched into the skins of the customer before that fateful day he reputedly walked past the window of an office supply shop on the Bowery, saw the Edison Pen in the window and walked in for a demonstration.

He was a very shrewd business man and must have checked with the U.S. Patent Office, the patent had expired on Edison's machine and so with a few minor alterations- the inclusion of an ink reservoir at the tip of the barrel and a change from the straight barrel to one with a couple of right angle bends that effectively moved the motor, and thus the weight, an inch and a half back over the hand (that would have cut back a little on the fatigue when using this device) also the needle bar could now accommodate a grand total of three needles - O'Reilly patented the first Electric Tattooing Machine on Dec. 8th 1891.

The world of tattooing would never be the same. The machine itself was not the revolutionary (pardon the pun) concept here, in fact it was simple and rather crude, but the idea that tattooing could be electrified and this notion changed the business forever.

This was the Industrial Revolution in full swing, mechanization was all the rage and inventors came up with new and faster ways to do almost everything. Electricity was a new force that could power motors or induce magnetism in a coil as used in telegraph machines and electric door bells. These door bell mechanisms were the basis for many of the early tattoo machines in Europe and simply had plates welded to them to hold the tubes and needle bars.

Tom Riley of London, England patented his electromagnetic coil machine on Dec. 28th 1891 twenty days after Sam O'Reilly filed his U.S. patent. Tom Riley's machine had a single coil and was a modified door bell assembly contained in a brass box.

George Burchett (the first tattoo artist to appear on television, BBC, 1938) bought his first electric tattoo machine from Riley and used it in his Mile End tattoo shop at the turn of the 20th century with great success. Later he improved the design (Patented London Dec. 13th 1904) to include a switch to stop the machine when changing colors, previous to this innovation tattoo machines just kept running until the battery was disconnected, and an external transformer to allow you to plug the machine into a wall outlet doing away with bulky glass and wooden batteries containing sulphuric acid.

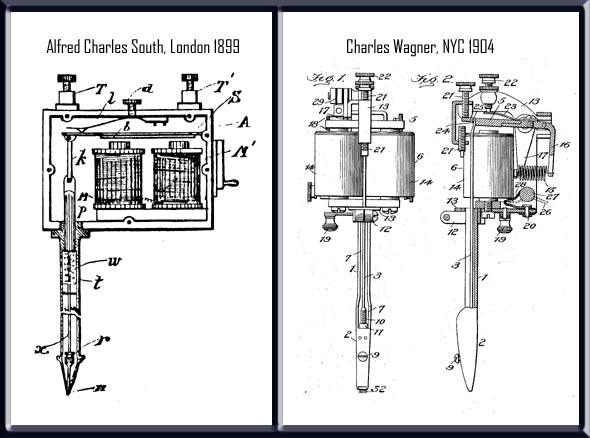

The first twin coil machine, the predecessor of the modern configuration, was invented by another Englishman, Alfred Charles South of Cockspur St. London (Patented London Jun. 30th 1899)

His construction was also based on a door bell assembly in a plate steel box with brass slabs attached to each side. It was heavy and was often used with a spring attached to the top of the machine and to the ceiling to take most of the weight off the operators' hand.

Burchett must have seen or used one of these contraptions as his improvements to the Tom Riley machine included two coils in the same configuration as Alfred South, one behind the other as in a modern machine.

The first American twin coil machine came five years after Alfred South's British patent from Charles Wagner of New York (Patented Aug. 23rd 1904,) which had the coils set side by side; transverse to the frame. The inspiration for this undoubtedly came from Thomas Edison and his improved engraving instruments as the coil placement and contact bars are very close in design. The two coils were set side by side as in a telegraph machine and required a cross shaped armature bar (the reciprocating metal bar that drives the needles up and down). This was not a simple machine to manufacture, but sold well to the professional tattooists and amateurs alike. Charlie Wagner worked closely with Samuel O'Reilly who had previous experience researching and adapting Edison's patents.

The inspiration for this undoubtedly came from Thomas Edison and his improved engraving instruments as the coil placement and contact bars are very close in design. The two coils were set side by side as in a telegraph machine and required a cross shaped armature bar (the reciprocating metal bar that drives the needles up and down). This was not a simple machine to manufacture, but sold well to the professional tattooists and amateurs alike. Charlie Wagner worked closely with Samuel O'Reilly who had previous experience researching and adapting Edison's patents.

Each of these early pioneers of tattooing technology saw the potential to market their devices to the profession and general public alike. The tattoo kit was born. Machines were sold though magazine ads with instructions, inks and a book of designs.

Manufactured goods spread around the world and tattoo machines were certainly bought and sold between the U.S.A. and Briton. The British twin coil machines made it to the U.S. as well did some of the best tattooists Briton had to offer, Tom Riley and Sutherland MacDonald, who also patented his own machine (Feb. 12th 1894) which was of a very different design consisting of a cylinder shaped electromagnetic coil through the center of which the needle bar passed. While tattooing in America, Riley had the honorary title of "Professor" bestowed upon him by P.T. Barnum and was the first tattooist to style himself in this way.

The machines were rudimentary, that is to say, they were designed to work as manufactured. No room for adjustment, no way to change the function of the machine, it drove a needle or combination of needles up and down at a set distance. The frames that held the parts together were purely a practicality.

In modern tattoo machine theory, the function of the machine is determined by the various angles and distances and their relationship to the elements of the machine. This is called the "frame geometry".

It is generally held true that a machine made to line a tattoo is set up differently from a shading machine. The frame geometry is changed and different effects in the skin are achieved, depth, power and speed are consequences of this equation and all parts relate to each other.

Up until 1929 the design considerations for tattoo machines were primarily weight, power source, coil size and orientation and fabrication material.

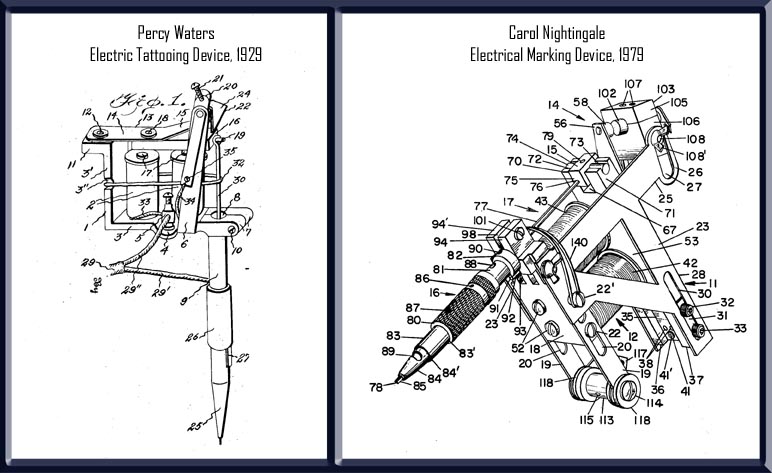

Percy Waters of Detroit, Michigan established probably the largest tattoo supply company in the world through the 1920s and 1930s. He designed and manufactured fourteen frame styles and patented what would become the first modern tattoo machine, in terms of frame geometry, on Aug. 13th 1929.

This tattoo machine design, and the other thirteen, is still in use today. Employing simple variations such as the angle of the contact screw; this is at the top of the machine and comes into contact with the springs determining the depth of the needle stroke, gave rise to a range of machines which can achieve different results when tattooing.

From Edison's puncturing machines of 1875, it took almost fifty-five years before someone figured out a tattoo machine could be adjusted and perhaps one needle depth was not always what the design needed to be tattooed successfully.

The shape, size and angles associated with the frame of the tattoo machine have a profound effect on the efficiency and performance of that machine.

Percy Waters set the bar for today's tattoo machines, the on/off switch that appeared on his patented machine has disappeared; it was right on top of the tube grip and could be pushed with the index finger. Early machines were not designed to be taken apart and cleaned. The tubes or barrels were frequently welded into place. Tube vices were a later development, and well in use by Percy Waters time.

It would be fifty years before another tattoo machine patent was granted by the U.S. Patent Office and in that time tattooing legends took the basic Waters designs and made them their own. Paul Rogers, Norman "Sailor Jerry" Collins, Milton Zeis, Owen Jensen and Bill Jones tweaked and tuned and turned them out by the score. Most of these designs are in production today. All of the originals are solid, workable instruments and highly collectible.

On July 3rd 1979 Carol Nightingale, a Canadian tattooist working in Washington D.C., patented his "Electrical Marking Device". When it comes to adjustability, this had it all. Every single component of the machine was adjustable. By turning a few screws you could slide the coils forward and backwards as well as the back springs, contact screw housing, armature bar etc. etc.

It was never a success, there were too many problems with the manufacturing processes and the machine was just too complicated. But it was inspired work. Taking the limitations of a set configuration and setting the operator free to tune the machine any which way they thought would work. Nightingale sold half a dozen or so.

The materials used to make the frames for tattoo machines have varied greatly over the years.

Iron, steel and brass were among the first used and prevail in modern machines. Bakelite, an early plastic that can be easily machined, has seen its share of popularity. Wooden frames were predominant as prototypes were developed in the early 1900s. Copper has seen a rise in interest in recent years even being combined with beryllium, a mildly radioactive metal that stabilizes when alloyed.

The advancement of technology will surely bring new and exciting developments to the tattoo machine. The recent interest, development and marketing of a pneumatic tattooing machine has been rather successful and is itself based on another Tom Edison patent- "The Edison Pneumatic Stencil Pen" (Jun. 25th 1878) proposed that air pressure, in this case from a compressor, would allow the machine to be lighter and easy to use.

There is nothing new under the sun.

Paul Roe

Washington DC

2005