Tattoo Techniques and Methods: Ancient and Modern

Originally written for Tattoodles.com in 2005 these articles detail the history of the tattoo machine, tattoo history and methods and health issues associated with tattooing.

The practice of marking the skin has been recorded in every culture all over the world. The methods used by different cultures are similar in that the result is to get the ink or pigment under the skin in such a way that it heals and is permanent.

The practices and tools used differ from one culture to the next and have changed over time with influence from outside societies. Let's start by thinking about the need to get that ink in; the skin is surprisingly strong and durable, water proof yet permeable, one of three methods can be used.

Pierce, puncture or cut.

Piercing the skin involves an object being pushed into the skin, sometimes being drawn out through the same hole.

Piercing; as a motion to introduce tattoo pigments into the skin, is generally but not exclusively done at an acute angle to the skin. This requires less force to penetrate the stacked cell structure and often this method allows a faster motion and less resistance.

Puncturing the skin is when an object is put through the surface which requires a relatively large amount of force.

As a protective barrier to our environment, the skin is an amazingly strong and resilient material; it must be waterproof yet permeable, flexible and durable. The tissue structure of stacked, cells provides an effective wall against most everyday strikes and scratches.

Cutting the skin, also scratching or scraping, divides the surface cell structure and gives access to the underlying cells. The flesh has a tendency to resist an object cutting through it and 'drag' may slow this method down.

The pigment must come into the equation at some point and this can be before, during of after the skin surface is breeched depending on the method used.

Piercing The Skin.

Some of the earliest tattooing needles date from the Upper Paleolithic period (10,000 BCE to 38,000 BCE)

Found at several archaeological digs around Europe, the sharpened bone needles pierced the skin easily and the pigment came from dipping the needle into holes in a disc of red ochre mixed with clay.

Needles made of fish and turtle bones have been excavated on American Indian land from The Plains Cree to the Mohave and the Yuma, of Arizona share similar patterns tattooed on the chins of the women, vertical stripes from one corner of the mouth to the other and varying in thickness according to the shape of the individuals face. It is also recorded that long thorns and splinters of rock, possibly flint, were used.

The ancient Egyptians tattooed the courtiers and concubines to the Pharos. Many mummies have been unwrapped to reveal elaborate patterns of dots and stripes around the waist, buttocks, legs and back. Needles of copper or bone and thorns would have been used to make these marks.

The sixth century Roman physician, Aetius, wrote "...prick the design with pointed needles until blood is drawn, then rub in the ink..." The Latin word stigma is defined by Webster as Latin and Greek in origin meaning a "tattoo mark, a prick with a pointed instrument, a mark of disgrace or reproach."

The Inuit tribes of Canada and Alaska also use a piercing method; however the needle has the same structure as a bone sewing needle and has an eye at the blunt end. A thread is strung through the eye and drawn across the ink to soak it. The needle is then sewn into the skin, up and down, up and down, pulled through and the pigment deposited in the channel left by the needle. This is highly skilled work and generally only practiced by the older women of the tribe. They have the extensive knowledge and experience gained through sewing animal skin clothing, boots and boat covers. To complete one line you must sew the first pass and then repeat to fill in the gaps between the stitches. The depth of penetration should be limited to allow the skin to hold the ink. Too deep and the immune system will flush the pigment as a foreign body, Too shallow and the skin will push out the ink through growth and cell replenishment.

The traditional Japanese method also is a piercing technique, known as Tebori; a group of needles is attached to a stick of bamboo, wood, ivory or various metals, and is held in one hand. The other hand holds the skin taught and the tool is placed between thumb and forefinger much in the same way a pool or snooker cue is held.

The needles are drawn back across the surface of the skin at an acute, shallow angle and then pushed forward to pierce the surface. This motion is repeated around 5 times a second in the hands of a master. The pigment is applied to the needles before they are pushed into the skin and one must dip into the ink, which may be on a brush held between the ring and small finger on the stretching hand, frequently.

The artist uses different needle groupings for different sized lines or for shading and coloring. This method is still used today and in the hands of a master can produce amazing subtleness of color blending and shade.

The ancient tools were often long and delicately sharpened ivory needles, intricately carved and works of art in their own right. Split bamboo or shell could be used for a wider distribution of ink.

The application of permanent make-up in beauty salons can be done by hand and this is similar to the Tebori method but using shorter hand tools. A needle groups is held in a short, stout handle and dipped into the pigment. The needles are rested on the skins surface, drawn back at an angle and pressed forward and up piercing the skin and placing the ink. The resulting sound is something close to cutting, or more accurately crushing, vegetables such as carrots. The disturbing sound aside this method is slow but virtually painless.

The application of permanent make-up in beauty salons can be done by hand and this is similar to the Tebori method but using shorter hand tools. A needle groups is held in a short, stout handle and dipped into the pigment. The needles are rested on the skins surface, drawn back at an angle and pressed forward and up piercing the skin and placing the ink. The resulting sound is something close to cutting, or more accurately crushing, vegetables such as carrots. The disturbing sound aside this method is slow but virtually painless.

The modern tattoo machine is a piercing and puncturing instrument. Groups of needles are driven up and down at various speeds (approx. 80-150 strokes per. second) into and out of the skin.

Resistance can be a factor if using larger groups of needles but tends to be negligible when an appropriate machine set up is used. Power and depth of penetration will depend on the individual machine and its operator's preferences. Modern tattooing is done a various angles to the skin dependent on the required results. Lining a tattoo generally happens at ninety degrees to the skin and coloring and shade at lower, more acute angles.

I relate the needle groups to my clients as "steel brushes", a fine line would be painted with a fine brush and a wider shaded area with a wider brush, the same thought process applies here. Three needles together in a tight point for a fine line and larger round groupings (eight, fourteen etc.) for shade and color. Flat needle configurations have the same use as do "magnums"; a double stack of flat needles reputably invented by Norman "Sailor Jerry" Collins in the 1940's.

The pigment is retained in a cone shaped reservoir at the tip of the tube and is deposited via a combination of injection (the needle pushes ink into the hole it's making) and suction (the ink is drawn into the hole as the needle is withdrawn).

Puncturing The Skin.

The difference between piercing and puncturing the skin lies in the angle at which the instrument enters and the force applied. Piercing requires a shallow angle and relatively little force. Puncturing, however, seems to take a disproportionate amount of energy.

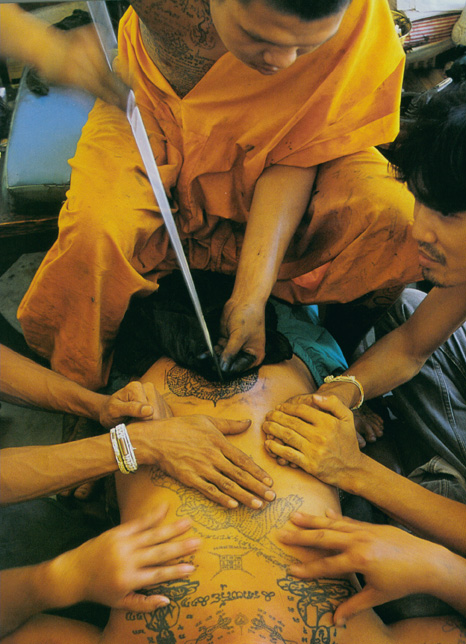

In Burma monks practice tattooing with a long, sometimes up to four feet in length, severely tapered, brass or even glass rods. This is guided through a brass sleeve which serves to steady the rod while it is repeatedly driven up and down inside the sleeve at a ninety degree angle to the skin with one hand. The instrument is dipped into the ink and then applied to the skin which must be stretched by assistants while being worked upon. The top of these rods often are decorated with animals and mythical creatures.

In Thailand the instrument is similar but no guide sleeve is used. Designs made this way can be seen to comprise of hundreds and thousands of dots punctured into the skin. There is a ritual still practiced in Thailand that uses a clear oil, which has been blessed, and is tattooed onto the shaved head of the participant, This oil will leave no mark when healed so one must conclude that it is done purely for the act of tattooing, the sacrifice of time, blood and the pain endured become the ritual results.

The Polynesian method is usually equated with the word tattoo; records show that the Polynesian practice was recorded before Captain James Cook coined the term in 1774.

Traditional tattooing tools consist of a comb with needles carved from bone, conch shell or tortoise shell, fixed to a wooden handle, this looks much like a small rake. The needles are dipped into the pigment and then placed on the skin and the handle is tapped with a second wooden stick, causing the comb to puncture the skin and insert the pigment.

In 1774, Captain Cook returning from his trip to the Marquises Islands wrote in his diary "they print signs on people's body and call this tattaw".

He did make some mistakes though when putting it into phonetic English. For a long time it has been thought that the word related to the sound of the sticks that beat the color into the skin. But with a little knowledge of the Tahitian language we understand it to be spelled ta-ta-u.

The double ta-ta does not relate to the sound, but to an act that is done with your hand (ta) and u means color. The repetitive ta-ta tells that your hands beat several times to get the color u into the skin. The Marquesan word is Tatau. It is also called tatau on the Island of Tonga, where the word means a picture

In 1721 Sir James Turner, a military historian, used the word tattoo to denote the beating of military drums that signaled the closing the canteen in garrison or camp.

The roots of 'tattoo' are from the mid 1500's and indicate a strike or tap (tap-toe). It is easy to see how the meaning of the Polynesian word 'tattau' could have been equated with striking or tapping.

This method requires two hands to administer so some helpers to stretch the skin being tattooed are needed. It can be excruciating and last for hours at a time. The needle combs vary in width from five points to fifty or so.

The Dayak tribes of Borneo use much the same instruments as the Polynesians and in the same fashion. Their sticks are a little shorter and the beating stick often has a hammer headed end which is intricately carved. Traditional designs are cut from wooden blocks and printed with ink on to the skin before being hammered over to tattoo the skin below. The tattoo instruments are stored in a special box also carved with protective images such as dragons and serpents.

Cutting The Skin.

Cutting, scratching and scraping the skin divides the skin cells and allows ink to be rubbed into the cut.

The Maoris of New Zealand have a long history of "Ta Moko"; intricate spirals and swirls tattooed on the face and body. The instruments used to create these designs are chisel shaped called "Uhi" and are made of greenstone or various animal bones the preferred bone material being from the albatross. The first pass is with a strait edged chisel (Uhi) to cut the design into the skin, followed by toothed edged Uhi. These are dipped in ink and struck with a mallet repeatedly to put the ink in the skin. A very painful process which must be done with no reaction from the receiver of the tattoo, it is the measure of their fortitude and bravery, if so much as a wince is shown the tattooing is stopped. An unfinished moko is a mark of disgrace and shame.

Ta Moko is also tattooed with instruments similar to those used in Borneo and Polynesia and modern tattoo machines are used today.

Cutting was also the preferred method for the native tribes of Virginia. The Roanoac, Secotam, Pomeiooc and Aquascogoc share a range of identifying tattoos in the shape of strait arrows and crosses which tell of their tribes and regional identity.

That's what it all boils down to, regardless of the method used; the results project our own identity.

And in each of these societies and cultures those applying the tattoos revere the process, the ritual, and of course the results. This ancient art is in our hands and it is our duty to pay it the respect it has earned through thousands of years of history and billions of tattoos applied.

Paul Roe

Washington DC

2005